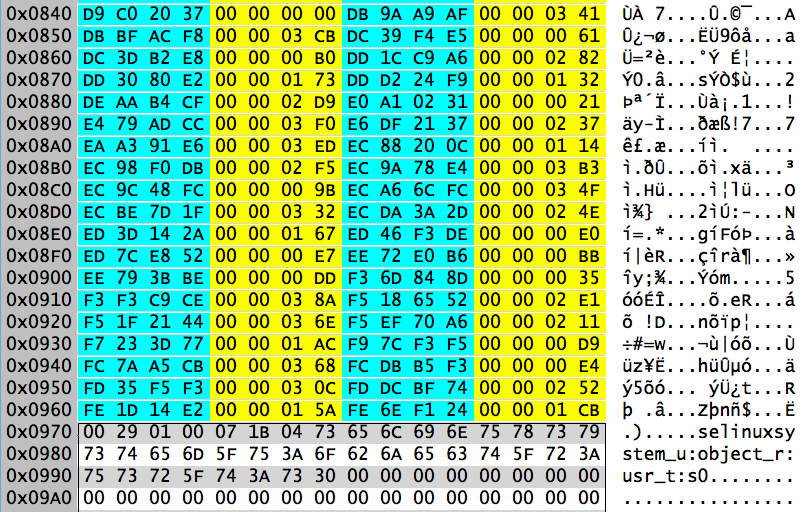

Many years ago I did a breakdown of the EXT4 file system. I devoted an entire blog article to the new timestamp system used by EXT4. The trick is that EXT4 added 32-bit nanosecond resolution fractional seconds fields in its extended inode. But you only need 30 bits to represent nanoseconds, so EXT4 uses the lower two bits of the fractional seconds fields to extend the standard Unix “epoch time” timestamps. This allows EXT4 to get past the Y2K-like problem that normal 32-bit epoch timestamps face in the year 2038.

At the time I wrote, “With the extra two bits, the largest value that can be represented is 0x03FFFFFFFF, which is 17179869183 decimal. This yields a GMT date of 2514-05-30 01:53:03…” But it turns out that I misunderstood something critical about the way EXT4 handles timestamps. The actual largest date that can be represented in an EXT4 file system is 2446-05-10 22:38:55. Curious about why? Read on for a breakdown of how EXT4 timestamps are encoded, or skip ahead to “Practical Applications” to understand why this knowledge is useful.

Traditional Unix File System Timestamps

Traditionally, file system times in Unix/Linux are represented as “the number of seconds since 00:00:00 Jan 1, 1970 UTC”– typically referred to as Unix epoch time. But what if you wanted to represent times before 1970? You just use negative seconds to go backwards.

So Unix file system times are represented as signed 32-bit integers. This gives you a time range from 1901-12-13 20:45:52 (-2**31 or 0x80000000 or -2147483648 seconds) to 2038-01-19 03:14:07 (2**31 - 1 or 0x7fffffff or 2147483647 seconds). When January 19th, 2038 rolls around, unpatched 32-bit Unix and Linux systems are going to be having a very bad day. Don’t try to tell me there won’t be critical applications running on these systems in 2038– I’m pretty much basing my retirement planning on consulting in this area.

What Did EXT4 Do?

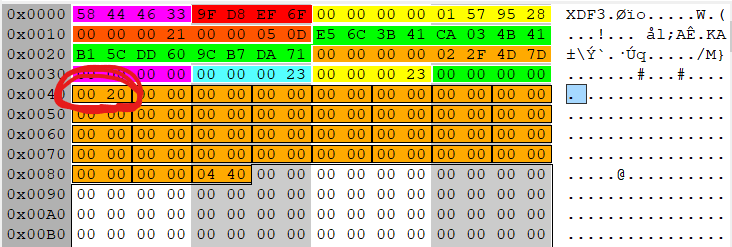

EXT4 had those two extra bits from the fractional seconds fields to play around with, so the developers used them to extend the seconds portion of the timestamp. When I wrote my infamous “timestamps good into year 2514” comment in the original article, I was thinking of the timestamp as an unsigned 34-bit integer 0x03ffffffff. But that’s not right.

EXT4 still has to support the original timestamp range from 1901 – 2038 and the epoch still has to be based around the January 1, 1970 or else chaos will ensue. So the meaning of the original epoch time values hasn’t changed. This field still counts seconds from -2147483648 to 2147483647.

So what about the extra two bits? With two bits you can enumerate values from 0-3. EXT4 treats these as multiples of 2*32 or 4294967296 seconds. So, for example, if the “extra” bits value was 2 you would start with 2 * 4294967296 = 8589934592 seconds and then add whatever value is in the standard epoch seconds field. And if that epoch seconds value was negative, you end up adding a negative number, which is how mathematicians think of subtraction.

This insanity allows EXT4 to cover a range from (0 * 4294967296 - 2147483648) aka -2147483648 seconds (the traditional 1901 time value) all the way up to (3 * 4294967296 + 2147483647) = 15032385535 seconds. That timestamp is 2446-05-10 22:38:55, the maximum EXT4 timestamp. If you’re still around in the year 2446 (and people are still using money) then maybe you can pick up some extra consulting dollars fixing legacy systems.

At this point you may be wondering why the developers chose this encoding. Why not just use the extra bits to make a 34-bit signed integer? A 34-bit signed integer would have a range from -2**33 = -8589934592 seconds to 2**33 - 1 = 8589934591 seconds. That would give you a range of timestamps from 1697-10-17 11:03:28 to 2242-03-16 12:56:31. Being able to set file timestamps back to 1697 is useful to pretty much nobody. Whereas the system the EXT4 developers chose gives another 200 years of future dates over the basic signed 34-bit date scheme.

Practical Applications

Why I am looking so closely at EXT4 timestamps? This whole business started out because I was frustrated after reading yet another person claiming (incorrectly) that you cannot set ctime and btime in Linux file systems. Yes, the touch command only lets you set atime and mtime, but touch is not the only game in town.

For EXT file systems, the debugfs command allows writing to inode fields directly with the set_inode_field command (abbreviated sif). This works even on actively mounted file systems:

root@LAB:~# touch MYFILE

root@LAB:~# ls -i MYFILE

654442 MYFILE

root@LAB:~# df -h .

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/mapper/LabVM-root 28G 17G 9.7G 63% /

root@LAB:~# debugfs -w -R 'stat <654442>' /dev/mapper/LabVM-root | grep time:

ctime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

atime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

mtime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

crtime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

root@LAB:~# debugfs -w -R 'sif <654442> crtime @-86400' /dev/mapper/LabVM-root

root@LAB:~# debugfs -w -R 'stat <654442>' /dev/mapper/LabVM-root | grep time:

ctime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

atime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

mtime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

crtime: 0xfffeae80:8eb89330 -- Tue Dec 30 19:00:00 1969The set_inode_field command needs the inode number, the name of the field you want to set (you can get a list of field names with set_inode_field -l), and the value you want to set the field to. In the example above, I’m setting the crtime field (which is how debugfs refers to btime). debugfs wants you to provide the value as an epoch time value– either in hex starting with “0x” or in decimal preceded by “@“.

What often trips people up when they try this is caching. Watch what happens when I use the standard Linux stat command to dump the file timestamps:

root@LAB:~# stat MYFILE

File: MYFILE

Size: 0 Blocks: 0 IO Block: 4096 regular empty file

Device: fe00h/65024d Inode: 654442 Links: 1

Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 0/ root)

Access: 2024-09-02 09:58:13.598615244 -0400

Modify: 2024-09-02 09:58:13.598615244 -0400

Change: 2024-09-02 09:58:13.598615244 -0400

Birth: 2024-09-02 09:58:13.598615244 -0400The btime appears to be unchanged! The inode value has changed, but the operating system hasn’t caught up to the new reality yet. Once I force Linux to drop it’s out-of-date cached info, everything looks as it should:

root@LAB:~# echo 3 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches

root@LAB:~# stat MYFILE

File: MYFILE

Size: 0 Blocks: 0 IO Block: 4096 regular empty file

Device: fe00h/65024d Inode: 654442 Links: 1

Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 0/ root)

Access: 2024-09-02 09:58:13.598615244 -0400

Modify: 2024-09-02 09:58:13.598615244 -0400

Change: 2024-09-02 09:58:13.598615244 -0400

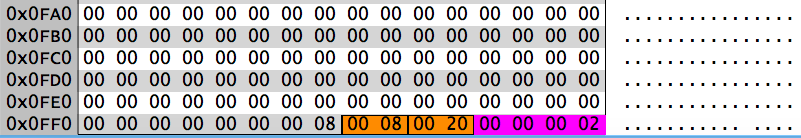

Birth: 1969-12-30 19:00:00.598615244 -0500If I wanted to set the fractional seconds field, that would be crtime_extra. Remember, however, that the low bits of this field are used to set dates far into the future:

root@LAB:~# debugfs -w -R 'sif <654442> crtime_extra 2' /dev/mapper/LabVM-root

root@LAB:~# debugfs -w -R 'stat <654442>' /dev/mapper/LabVM-root | grep time:

debugfs 1.46.2 (28-Feb-2021)

ctime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

atime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

mtime: 0x66d5c475:8eb89330 -- Mon Sep 2 09:58:13 2024

crtime: 0xfffeae80:00000002 -- Tue Mar 15 08:56:32 2242For the *_extra fields, debugfs just wants a raw number either in hex or decimal (hex values should still start with “0x“).

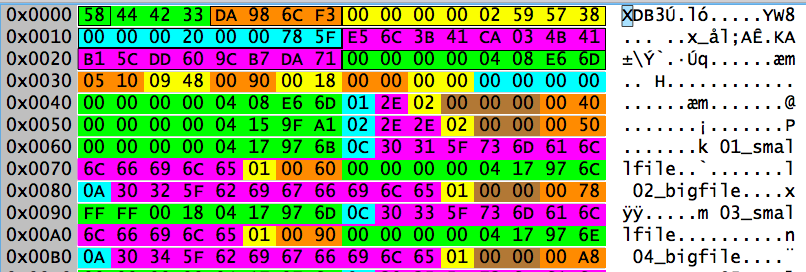

Making This Easier

Human beings would like to use readable timestamps rather than epoch time values. The good news is that GNU date can convert a variety of different timestamp formats into epoch time values:

root@LAB:~# date -d '2345-01-01 12:34:56' '+%s'

11833925696Specify whatever time string you want to convert after the -d option. The %s format means give epoch time output.

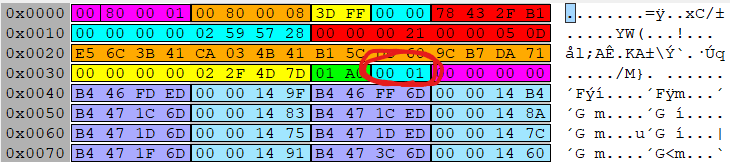

Now for the bad news. The value that date outputs must be converted into the peculiar encoding that EXT4 uses. And that’s why I spent so much time fully understanding the EXT4 timestamp format. That understanding leads to some crazy shell math:

# Calculate a random nanoseconds value

# Mask it down to only 30 bits, shift right two bits

nanosec="0x$(head /dev/urandom | tr -d -c 0-9a-f | cut -c1-8)"

nanosec=$(( ($nanosec & 0x3fffffff) << 2) ))

# Get an epoch time value from the date command

# Adjust the time value to a range of all positive values

# Calculate the number for the standard seconds field

# Calculate the bits needed in the *_extra field

epoch_time=$(date -d '2345-01-01 12:34:56' '+%s)

adjusted_time=$(( $epoch_time + 2147483648 ))

time_lowbits=$(( ($adjusted_time % 4294967296) - 2147483648 ))

time_highbits=$(( $adjusted_time / 4294967296 ))

# The *_extra field value combines extra bits with nanoseconds

extra_field=$(( $nanosec + $time_highbits ))Clearly nobody wants to do this manually every time. You just want to do some timestomping, right? Don’t worry, I’ve written a script to set timestamps in EXT:

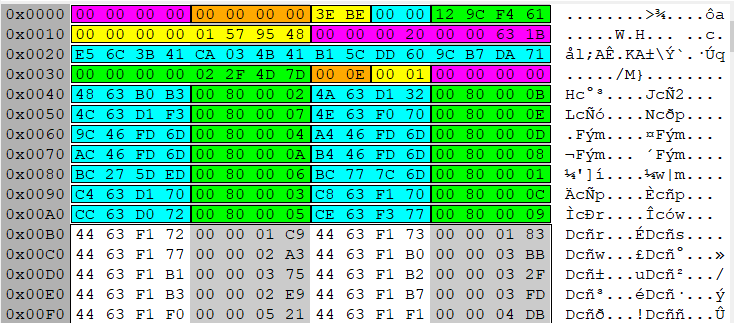

root@LAB:~# extstomp -v -macb -T '2123-04-05 1:23:45' MYFILE

===== MYFILE

ctime: 0x2044c7e1:ec154f7d -- Mon Apr 5 01:23:45 2123

atime: 0x2044c7e1:ec154f7d -- Mon Apr 5 01:23:45 2123

mtime: 0x2044c7e1:ec154f7d -- Mon Apr 5 01:23:45 2123

crtime: 0x2044c7e1:ec154f7d -- Mon Apr 5 01:23:45 2123

root@LAB:~# extstomp -v -cb -T '2345-04-05 2:34:56' MYFILE

===== MYFILE

ctime: 0xc1d6b290:61966bab -- Thu Apr 5 02:34:56 2345

atime: 0x2044c7e1:ec154f7d -- Mon Apr 5 01:23:45 2123

mtime: 0x2044c7e1:ec154f7d -- Mon Apr 5 01:23:45 2123

crtime: 0xc1d6b290:61966bab -- Thu Apr 5 02:34:56 2345Use the -macb options to specify the timestamps you want to set and -T to specify your time string. You can use -e to specify nanoseconds if you want, otherwise the script just generates a random nanoseconds value. The script is usually silent but -v causes the script to output the file timestamps when it’s done. The script even drops the file system caches automatically for you (unless you use -C to keep the old cached info).

And because you often want to blend in with other files in the operating system, I’ve included an option to copy the timestamps from another file:

root@LAB:~# extstomp -v -macb -S /etc/passwd MYFILE

===== MYFILE

ctime: 0x66b37fc9:9d8e0ba8 -- Wed Aug 7 10:08:09 2024

atime: 0x66d5c3cb:33dd3b30 -- Mon Sep 2 09:55:23 2024

mtime: 0x66b37fc9:9d8e0ba8 -- Wed Aug 7 10:08:09 2024

crtime: 0x66b37fc9:9d8e0ba8 -- Wed Aug 7 10:08:09 2024

root@LAB:~# stat /etc/passwd

File: /etc/passwd

Size: 2356 Blocks: 8 IO Block: 4096 regular file

Device: fe00h/65024d Inode: 1368805 Links: 1

Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 0/ root)

Access: 2024-09-02 09:55:23.217534156 -0400

Modify: 2024-08-07 10:08:09.660833002 -0400

Change: 2024-08-07 10:08:09.660833002 -0400

Birth: 2024-08-07 10:08:09.660833002 -0400You’re welcome!

What About Other File Systems?

It’s particularly easy to do this timestomping on EXT because debugfs allows us to operate on live file systems. In “expert mode” (xfs_db -x), the xfs_db tool has a write command that allows you to set inode fields. Unfortunately, by default xfs_db does not allow writing to mounted file systems. Of course, an enterprising individual could modify the xfs_db source code and bypass these safety checks.

And that’s really the bottom line. Use the debugging tool for whatever file system you are dealing with to set the timestamp values appropriately for that file system. It may be necessary to modify the code to allow operation on live file systems, but tweaking timestamp fields in an inode while the file system is running is generally not too dangerous.

:

: