In my earlier write-ups on XFS, I noted that when a file is deleted:

- The inode address is often still visible in the deleted directory entry

- The extent structures in the inode are not zeroed

This combination of factors should make it straightforward to recover deleted files. Let’s see if we can document this recovery process, shall we?

For this example, I created a directory containing 100 JPEG images and then deleted 10 images from the directory:

We will be attempting to recover the 0010.jpg file. I have included the file checksum and output of the file command in the screenshot above for future reference.

Examining the Directory

I will use xfs_db to dump the directory file. But first I need to know the device that contains the file system and the inode number of our test directory:

LAB# mount /images

mount: /images: /dev/sdb1 already mounted on /images.

LAB# ls -id /images/testdir/

171 /images/testdir/

LAB# xfs_db -r /dev/sdb1

xfs_db> inode 171

xfs_db> print

core.magic = 0x494e

[... snip ...]

v3.crtime.sec = Sun Jun 23 12:43:20 2024

v3.crtime.nsec = 240281066

v3.inumber = 171

v3.uuid = 82396b5c-3a48-46e9-b3fa-fbed705313b0

v3.reflink = 0

v3.cowextsz = 0

u3.bmx[0] = [startoff,startblock,blockcount,extentflag]

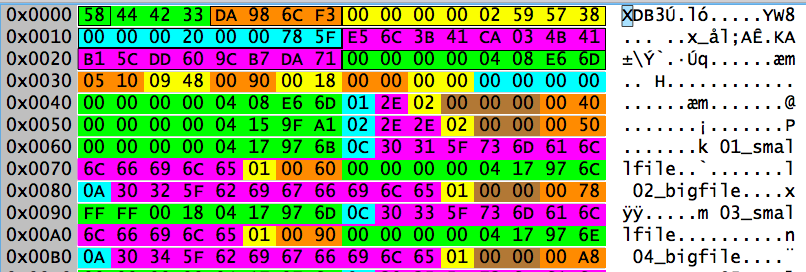

0:[0,2315557,1,0]The directory file occupies a single block at address 2315557. We can use xfs_db to dump the contents of that block. Viewing the block as a directory isn’t all that helpful, though we can see the area of deleted directory entries in the output:

xfs_db> fsblock 2315557

xfs_db> type dir3

xfs_db> print

bhdr.hdr.magic = 0x58444233

[... snip ... ]

bu[10].namelen = 8

bu[10].name = "0009.jpg"

bu[10].filetype = 1

bu[10].tag = 0x120

bu[11].freetag = 0xffff

bu[11].length = 0xf0

bu[11].filetype = 1

bu[11].tag = 0x138

bu[12].inumber = 20049168

bu[12].namelen = 8

bu[12].name = "0020.jpg"

bu[12].filetype = 1

bu[12].tag = 0x228

bu[13].inumber = 20049169

bu[13].namelen = 8

bu[13].name = "0021.jpg"

[... snip ...]Array entry 11 shows the 0xffff marker that denotes the beginning of one or more deleted directory entries, and then we have the two-byte length value (0x00f0 or 240 bytes) of the length of that section.

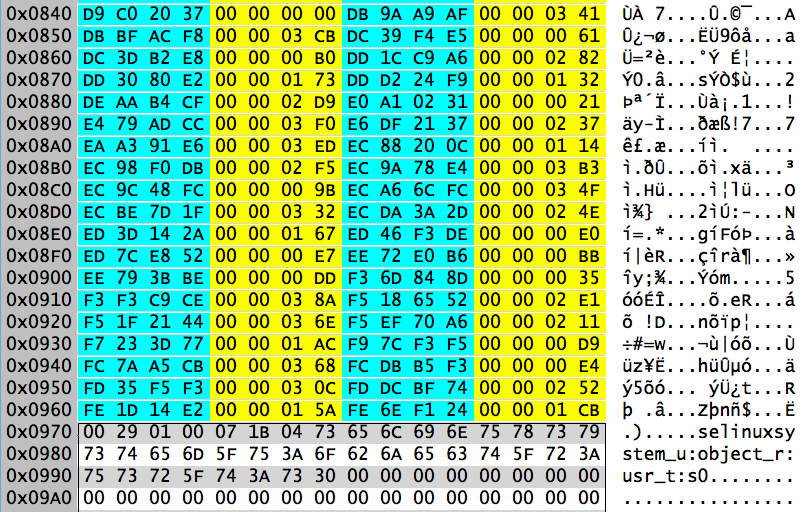

But to see the actual contents of that region, we will need to get a hex dump view:

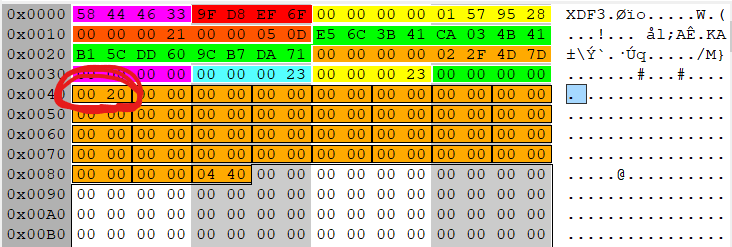

At offset 0x138 you can see the “ff ff” marking the start of the deleted entries and the “00 f0” length value. These four bytes overwrite the upper four bytes of the inode address of the 0010.jpg file, but the lower four bytes are still visible: “01 31 ed 06“.

Recall from my previous XFS write-ups that while XFS uses 64-bit addresses, the block and inode addresses are variable length and rarely occupy the entire 64-bit address space. The inode address length is based on the number of blocks in each allocation group, and the number of bits necessary to represent that many blocks. This is the agblklog value in the superblock:

xfs_db> sb 0

xfs_db> print agblklog

agblklog = 2424 bits are required for the relative block offset in the AG. We need three additional bits to index the inode within the block– 27 bits in total. Everything above these 27 bits is the AG number, but assuming the default of four AGs per file system, the AG number only occupies two more bits. The inode address should fit in 29 bits, and so the inode residue we are seeing in the directory entry should be the entire original inode address. You can confirm this by looking at the deleted directory entries that follow the deleted 0010.jpg file— their upper 32 bits are untouched and they show all zeroes in the upper bits.

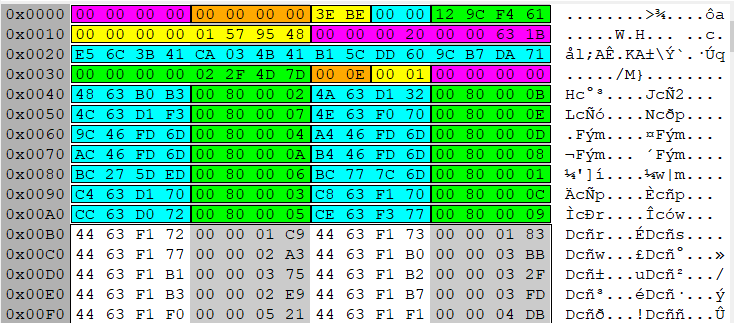

Examining the Inode

We have some confidence that the inode of the deleted 0010.jpg file is 0x0131ed06. We can use xfs_db to examine this inode. The normal output from xfs_db shows us that the file is empty and there are no extents:

xfs_db> inode 0x0131ed06

xfs_db> print

core.magic = 0x494e

[... snip ...]

core.size = 0

core.nblocks = 0

core.extsize = 0

core.nextents = 0

core.naextents = 0

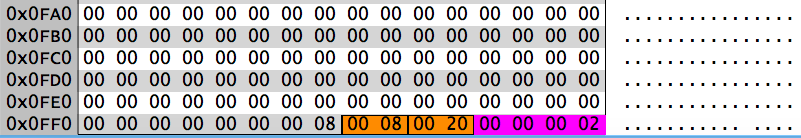

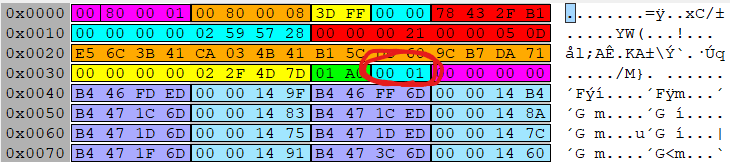

[... snip ...]However, viewing a hexdump of the inode shows the original extent structures:

The extents start at offset 0x0b0, immediately following the “inode core” region. Extents structures are 128 bits in length, so each line in the standard hexdump output format represents a single extent.

Recognizing that the standard, non-byte-aligned XFS extent structures are difficult to decode, I developed a small script called xfs-extents.sh that reads the extent structures from an inode and outputs dd commands that should dump the blocks specified in the extent. Simply provide the device name and the inode number:

LAB# xfs-extents.sh /dev/sdb1 0x0131ed06

(offset 0) -- dd if=/dev/sdb1 bs=4096 skip=$((0 * 12206976 + 2507998)) count=8

LAB# dd if=/dev/sdb1 bs=4096 skip=$((0 * 12206976 + 2507998)) count=8 >/tmp/recovered-0010.jpg

8+0 records in

8+0 records out

32768 bytes (33 kB, 32 KiB) copied, 0.00100727 s, 32.5 MB/s

LAB# file /tmp/recovered-0010.jpg

/tmp/recovered-0010.jpg: JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01, resolution (DPI), density 99x98, segment length 16, Exif Standard: [TIFF image data, big-endian, direntries=0], comment: "Created with GIMP", baseline, precision 8, 312x406, components 3

LAB# md5sum /tmp/recovered-0010.jpg

637ad57a1e494b2c521b959de6a1995e /tmp/recovered-0010.jpgThe careful reader will note that the MD5 checksum on the recovered file does not match the checksum of the original file. This is due to the fact that the recovered file includes the null-filled slack space at the end of the final block that was ignored in the original checksum calculations. Unfortunately the original file size in the inode is zeroed when the file is deleted, so we have no idea of the exact length of the original file. All we can do is recover the entire block run of the file, including the slack space. We should still be able to view the original image in this case, even with the extra nulls tacked on to the end of the file.

Extra Credit Math Problem

With the help of xfs_db and my little shell script, we were able to recover the deleted file. However, retrieving the inode from the deleted directory entry was facilitated by the fact that the inode address was less than 32 bits long. So even though the upper 32 bits of the 64 address space was overwritten, we could still see the original inode number.

Since the length of the inode address is based on the number of blocks per AG, the question becomes how large the file system has to grow before the inode address, including the AG number in the upper bits, becomes longer than 32 bits? Once this happens, recovering the original inode address from deleted directory entries becomes problematic– at least for the first entry in a region of deleted directory entries. Remember from our example above the full 64-bit address space of the second and later deleted entries in the chunk are fully visible.

We need two bits to represent the AG number in a typical XFS file system, and three bits to represent the inode offset in the block. That leaves 27 of 32 bits for the relative block offset in the AG. So the maximum AG size is 2**28 – 1 or 268,435,455 blocks. Assuming the standard 4K block size, that’s 1024 gigabytes per AG, or a 4TB file system.

What if we were willing to sacrifice the upper two bits of AG number? After all, even if the AG number were overwritten, we could still try to find our deleted file simply by checking the relative inode address in each of the AGs until we find the file we’re looking for. With an extra two bits of room for the relative block offset, each AG could now be four times larger allowing us to have up to a 16TB file system before the relative inode address was larger than 32 bits.

:

: